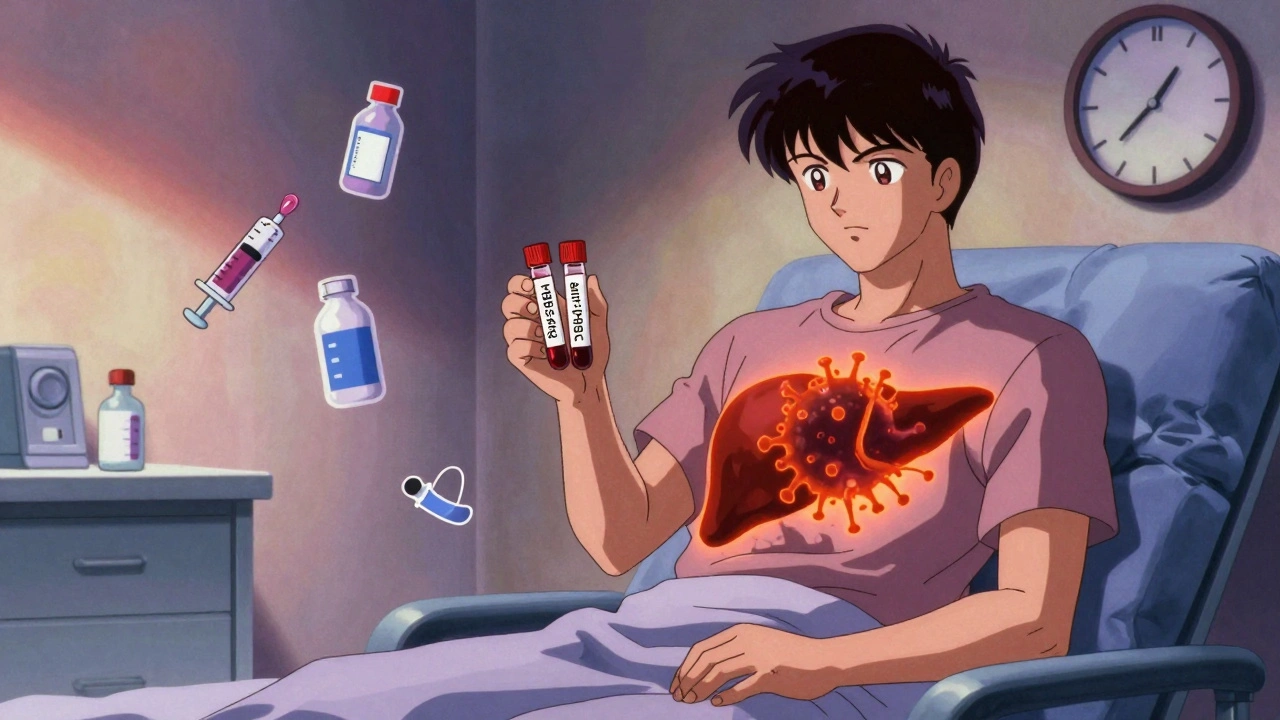

Every year, thousands of cancer patients and people with autoimmune diseases start powerful treatments like rituximab, chemotherapy, or TNF inhibitors. They’re fighting lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, or Crohn’s disease - but few know that one hidden threat could shut down their liver before they even finish their first cycle. That threat is HBV reactivation.

HBV reactivation isn’t a new infection. It’s when a dormant hepatitis B virus, buried in your liver for years, wakes up because your immune system gets knocked out by drugs. It can turn a quiet, harmless carrier state into acute liver failure - sometimes within weeks. And here’s the scary part: it’s almost always preventable.

What Exactly Is HBV Reactivation?

HBV reactivation happens when someone who once had hepatitis B - even if they never showed symptoms - gets treated with drugs that suppress the immune system. Their body can’t keep the virus in check anymore. The virus starts copying itself rapidly, and then the immune system tries to fight back. That fight damages the liver, causing jaundice, extreme fatigue, and in 5-10% of cases, death.

This isn’t theoretical. In the 1970s, doctors noticed patients getting sick after chemotherapy. By the 1990s, with the rise of biologics like rituximab, the pattern became undeniable. A 2016 study in Blood found that 73% of HBV-positive lymphoma patients on rituximab had viral reactivation if they weren’t on antivirals. That’s more than 7 out of 10. And that’s just one drug.

The virus doesn’t care if you’re in remission. It doesn’t care if your last blood test was normal. All it needs is a weak immune system - and plenty of modern treatments provide exactly that.

Who’s at Risk? The Real Risk Groups

Not everyone is equally at risk. Your risk depends on two things: your HBV status and the drug you’re taking.

High-risk patients: Those who are HBsAg-positive - meaning the virus is still active in their blood. These people have a 20-81% chance of reactivation, depending on the treatment. For example:

- Patients on anti-CD20 drugs like rituximab: 38-73% risk

- Those getting stem cell transplants: up to 81% risk

- People on anthracycline chemo: 25-40% risk

Moderate-risk patients: Those who are HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive. This means they cleared the virus years ago, but traces remain in their liver. Their risk is lower - 1-18% - but still real. A 2020 study in Journal of Clinical Oncology found 18% of these patients reactivated after high-dose chemo. That’s nearly 1 in 5. And many doctors still miss this group.

Low-risk patients: People who are negative for both HBsAg and anti-HBc. Their risk is near zero. No screening needed.

Even radiation therapy carries risk. A 2020 study showed a 14% reactivation rate in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive liver cancer patients after radiation. And checkpoint inhibitors - the new immunotherapy drugs like Keytruda - caused reactivation in 21% of HBsAg-positive patients who weren’t on antivirals, according to Hepatology in 2019.

The Screening Protocol: Simple, Cheap, Life-Saving

The solution isn’t complicated. It’s screening. Just two blood tests, done before any immunosuppressive therapy starts.

- HBsAg - tells you if the virus is currently active

- anti-HBc - tells you if you’ve ever been infected

That’s it. No ultrasound. No biopsy. No expensive panels. Just two simple tests. Cost? Under $50 in most places. Time? Five minutes.

Yet, a 2020 survey found only 58% of community oncologists follow this basic step. Why? Lack of awareness. Lack of systems. Too many doctors assume their patients are low-risk because they’re from a country with low HBV rates. But HBV doesn’t care where you’re from - it only cares if your liver carries the virus.

Dr. Robert G. Gish of the Hepatitis B Foundation says it plainly: “The cost of screening is negligible compared to the human and financial costs of managing reactivation.” And he’s right. One case of liver failure can cost over $200,000 in hospital bills - not counting lost wages, transplant costs, or death.

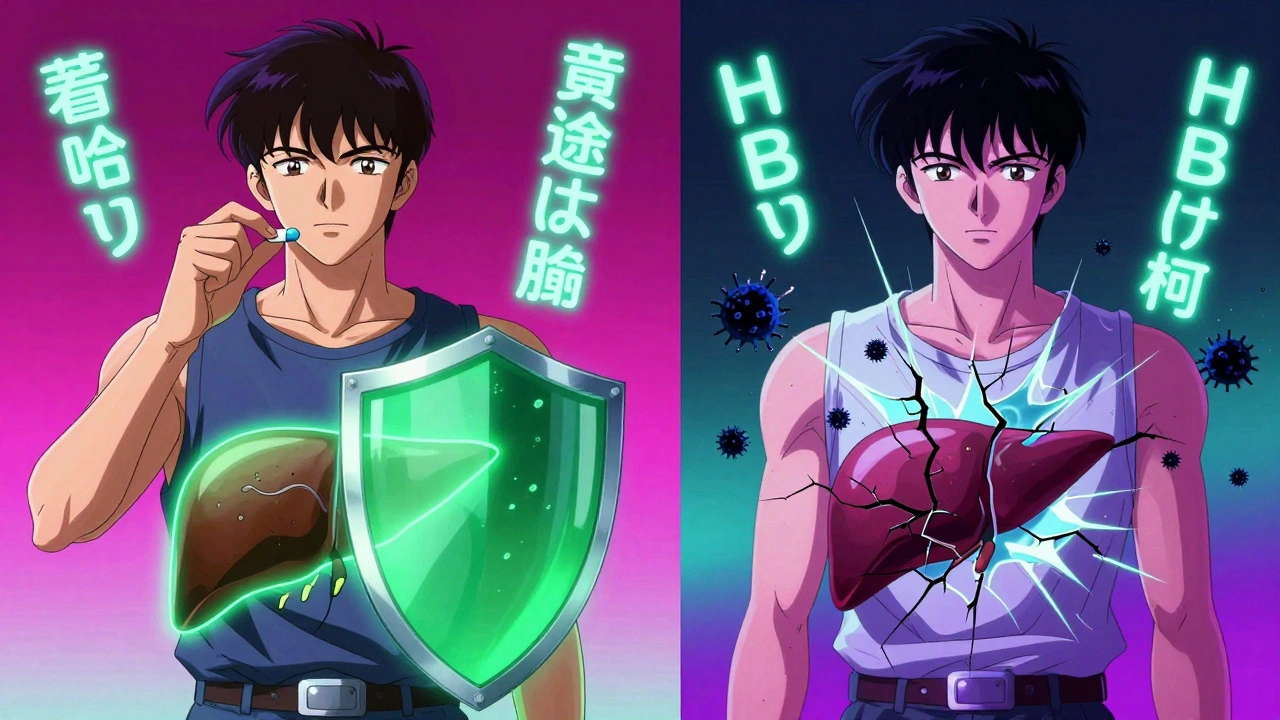

Prophylaxis: The Antiviral Shield

If you’re HBsAg-positive or anti-HBc-positive and about to start high-risk therapy, you need antiviral drugs - not as a treatment, but as a shield.

The two go-to drugs are tenofovir and entecavir. Both are taken as one pill a day. Both are safe, effective, and have minimal side effects. Neither causes weight gain, fatigue, or nausea like older drugs did.

Studies show they cut reactivation risk from over 40% down to under 5%. In one study of 1,245 patients, those on entecavir had a 3.2% reactivation rate. Those not on it? 48.7%. That’s a 93% reduction.

Timing matters. Start the antiviral at least one week before your first chemo or biologic dose. Keep it going during treatment. And don’t stop too soon. For high-risk drugs like rituximab or stem cell transplants, guidelines now say continue for 6-12 months after therapy ends. A 2022 New England Journal of Medicine study showed six months is enough for most cases - a big change from the old 12-month rule.

But here’s the catch: many patients stop the pills early because they feel fine. Or their oncologist forgets to remind them. That’s when reactivation sneaks back in.

What About Checkpoint Inhibitors and Newer Drugs?

Immunotherapy drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab are game-changers for cancer. But they’re also unpredictable. Unlike chemo, which knocks down the immune system, checkpoint inhibitors let it loose - sometimes too loose.

That means two problems:

- HBV can reactivate because the immune system can’t control it

- And the liver damage might look like immune-related hepatitis - not HBV

Dr. Joseph Ahn at Northwestern warns: “We’ve seen patients misdiagnosed because doctors thought it was a side effect of Keytruda, not HBV reactivation.”

That’s why even if you’re HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive and starting immunotherapy, you still need monitoring. Some experts now recommend prophylaxis for all HBsAg-positive patients on checkpoint inhibitors - no exceptions.

Why Do So Many People Still Get Missed?

It’s not ignorance. It’s systems failure.

At academic hospitals, EHR alerts trigger automatically when a patient is scheduled for rituximab. Nurses check HBV status before the infusion. Everyone knows the protocol.

At community clinics? Not so much. A 2022 study found 41% of community oncology practices still have no written HBV screening policy. No alerts. No checklists. No training.

Patients get referred from their PCP to an oncologist. The oncologist orders chemo. The lab order doesn’t include HBV screening. The patient doesn’t know to ask. Three weeks later, they’re in the ER with jaundice.

UCSF fixed this by adding an automated EHR alert: “HBV screening required before starting immunosuppressive therapy.” Within five years, their reactivation rate dropped from 12.3% to 1.7%.

It’s not magic. It’s just a checklist.

What Happens If You Don’t Screen?

Case reports tell the real story.

A 52-year-old man with lymphoma started rituximab without being screened. He had no symptoms. No history of liver disease. Two weeks later, he collapsed with liver failure. He died within days. Autopsy showed massive HBV reactivation.

Another patient, a 45-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis, started a TNF inhibitor. She’d never been told she had HBV. Her anti-HBc was positive. She didn’t get antivirals. Three months later, she needed a liver transplant.

These aren’t rare. They’re preventable.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America says bluntly: “Failure to screen results in preventable mortality.”

What You Can Do - Right Now

If you’re about to start chemotherapy, a biologic, or any immunosuppressive therapy:

- Ask your doctor: “Have I been screened for hepatitis B?”

- If they say no, ask for HBsAg and anti-HBc tests - now.

- If you test positive for either, ask: “Will I need antiviral prophylaxis?”

- If yes, make sure you know how long to take the pills - and don’t stop early.

- Keep a copy of your results. Share them with every new doctor.

If you’re a healthcare provider:

- Build HBV screening into your standard workup for any immunosuppressive therapy.

- Use EHR alerts if you can.

- Train your staff. Even nurses and medical assistants should know the two tests.

- Don’t assume low prevalence means low risk. HBV is silent until it’s not.

The Bottom Line

HBV reactivation is one of the most preventable disasters in modern medicine. We have the tests. We have the drugs. We have the guidelines. What we’re missing is consistent action.

Every time a patient gets chemo without screening, it’s not bad luck. It’s a system failure. And every time a patient gets antivirals before treatment - and stays healthy - it’s a win for common sense.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Ask for the test. Know your status. Protect your liver - before it’s too late.

12 Comments

Just had my first chemo last month and honestly? I had no clue about HBV screening. My oncologist didn’t mention it, but after reading this, I called their office and demanded the tests. Turns out I’m anti-HBc positive. They started me on entecavir right away. Feels weird taking a pill for something that’s been sleeping in my liver for decades, but I’d rather be safe than sorry. Thanks for the wake-up call!

HBsAg antiHBc screening mandatory before any immunosuppressant. Period. No excuses. 73% reactivation rate on rituximab without prophylaxis is criminal negligence. Most community docs still operate like it’s 1995. EHR alerts should be auto-triggered. If your clinic doesn’t have it, find a new one.

bro i got my anti-hbc done last year after my aunt got liver failure from chemo 😭 i was like wait what?? my doc never told me anything. now i’m on tenofovir and honestly it’s just one pill a day no big deal. but why do docs even forget this?? it’s like checking for blood type before surgery. basic stuff lol 🤦♂️

This is such an important post. I’m a med student and we barely touched on this in hepatology rotation. The fact that checkpoint inhibitors can cause reactivation even in anti-HBc+ patients is wild. I just added a sticky note to my notebook: ‘Always screen before immunosuppression.’ 🙌 Also, tenofovir and entecavir are so safe-like, you could take them for years without issues. Why isn’t this in every oncology protocol?

Let’s be brutally honest: the medical system is not designed to prevent harm-it’s designed to respond to it. We have a $200,000 liver failure crisis because we refuse to spend $50 on a blood test. This isn’t about awareness. It’s about institutional inertia. The profit model of healthcare incentivizes treatment over prevention. And until we restructure the entire paradigm, people will keep dying from things that are literally preventable with a clipboard and a lab slip. You’re not just asking for a test-you’re asking for moral integrity from a system that has long abandoned it.

Oh great. So now I have to take a pill for a virus I didn’t even know I had… just because some rich guy in a lab coat decided my immune system might get ‘too weak’? 🙄 I’m not a lab rat. I’ve been fine for 30 years. Why should I be punished for someone else’s negligence?

I’m from the Midwest. We don’t get hepatitis B here. My whole family’s clean. Why am I being treated like I’m from Asia? This feels like medical racism. I’m not getting tested. I’m not taking pills. I’m not letting some algorithm decide my health based on my ethnicity. I’m not a statistic.

My mom’s on rituximab for RA. She’s 68 and terrified. I printed out this whole thing and took it to her appointment. The nurse actually cried and said they never screen for this either. We’re getting the tests done tomorrow. I’m so mad. Why does this not just… happen? It’s like everyone’s pretending this doesn’t exist. I’m telling everyone I know.

The ethical imperative is unambiguous. The absence of standardized HBV screening protocols constitutes a systemic violation of the principle of non-maleficence. The cost-benefit analysis is not merely favorable-it is unequivocally optimal. The continued failure to implement mandatory screening in community settings is not merely a lapse in clinical practice; it is a dereliction of professional duty. The mortality rate is not incidental-it is preventable. And in medicine, preventable death is indefensible.

Man, I used to work in a clinic that didn’t screen. We had a guy die. Just… gone. Three weeks after his first infusion. No warning. No chance. After that, we made a checklist: HBsAg? Anti-HBc? Yes or no? If yes, antiviral script printed and handed to patient before they leave the room. Now? Zero reactivations in 4 years. It’s not rocket science. It’s just… doing the damn thing. And yeah, if you’re on Keytruda and anti-HBc+, you still need to be watched like a hawk. These drugs are powerful-but they’re not magic.

Let’s be real: if you’re not screening, you’re not a doctor-you’re a lottery ticket vendor. You’re betting your patient’s life against a $50 test. And if you’re okay with those odds, you shouldn’t be holding a stethoscope. You should be selling scratch-offs at a gas station. This isn’t medicine. It’s negligence dressed in a white coat.

So… if I’m anti-HBc+ and I’m getting chemo… I need to take a pill for 6-12 months AFTER? And my doc might forget to tell me? 😅 Well then I guess I’ll just… Google it? Like a normal person. Who knew medicine was just a game of ‘find the hidden checklist’? 🤷♀️