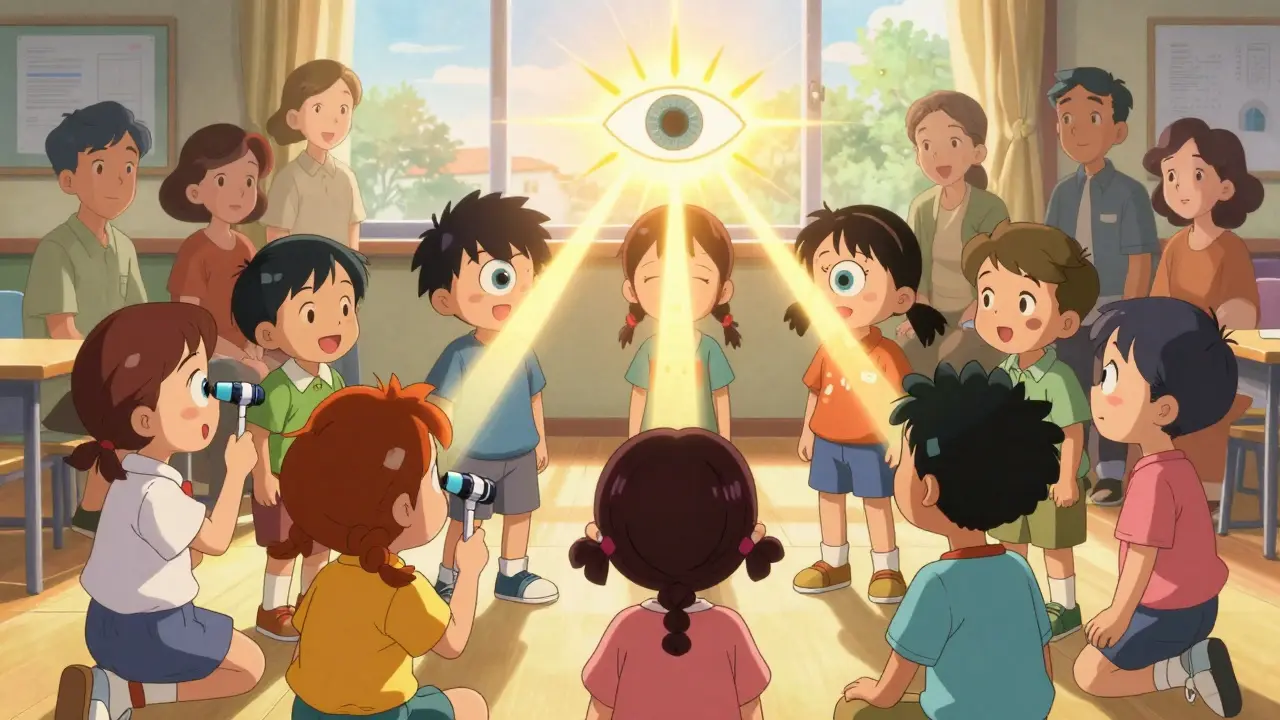

Every year, thousands of children in the U.S. grow up with undiagnosed vision problems that could have been fixed easily-if only someone had looked early enough. Amblyopia, or lazy eye, affects 1.2% to 3.6% of kids. Strabismus, where the eyes don’t line up, shows up in nearly 2% to 3.4%. These aren’t rare. And left untreated, they can cause permanent vision loss. The good news? Pediatric vision screening catches most of these issues before they stick. The even better news? When caught before age 5, 80% to 95% of kids with amblyopia can regain normal vision. After age 8? That number drops to just 10% to 50%.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Is Non-Negotiable

The human eye doesn’t fully develop until around age 7. During those early years, the brain is learning how to process what the eyes see. If one eye is blurry, crossed, or misaligned, the brain starts ignoring it. That’s how amblyopia forms. Once the brain shuts off input from that eye, it’s hard to bring it back online. That’s why timing matters more than anything else. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) gives pediatric vision screening a Grade B recommendation-meaning there’s strong evidence it works. They say: screen every child between ages 3 and 5. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a medical standard. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) agrees. Their Bright Futures guidelines list vision screening as a required part of well-child visits at ages 3, 4, and 5. This isn’t about checking if a child can read letters. It’s about catching problems before the brain learns to ignore them. A child might not complain. They don’t know what normal vision feels like. That’s why screenings must be routine-not optional.What Happens During a Vision Screening?

Screening methods change based on age. There’s no one-size-fits-all test. For babies under 6 months, doctors do a red reflex test. They shine a light into each eye using an ophthalmoscope. A healthy eye reflects a bright red glow. If one eye looks dark, white, or uneven, it could mean a cataract, retinoblastoma, or other serious issue. This test takes seconds but can save a child’s sight-or life. From 6 months to 3 years, screening includes checking eye movement, pupil response, and eyelid health. If a child’s eyes don’t track together, or one drifts outward or inward, that’s a red flag for strabismus. Parents might notice this at home, but many don’t. That’s why trained providers need to look. At age 3, kids start using eye charts. But not the big Snellen chart you see in an optometrist’s office. Instead, they use LEA Symbols (circles, squares, apples, houses) or HOTV letters (H, O, T, V). These are easier for young kids to recognize. The goal isn’t perfect vision-it’s catching significant problems. At age 3, a child must read the 20/50 line. At age 4, it’s 20/40. By age 5, they should hit 20/32 on a Sloan or LEA chart. Each eye is tested separately. A patch or paddle covers one eye while the child identifies symbols. The chart must be at eye level and lit properly. Too dim? You’ll miss problems. Too far? You’ll get false positives. The distance? Exactly 10 feet for distance testing. No guessing.Instrument-Based Screening: The New Standard for Young Kids

Not every 3-year-old will sit still for an eye chart. That’s where instrument-based screening comes in. Devices like the SureSight, Power Refractor, and blinq™ scanner measure how light reflects off the retina to detect refractive errors, misalignment, and asymmetry between eyes. These tools don’t need the child to say anything. They just look at the screen for a few seconds. The blinq™ scanner, FDA-cleared in 2018, has shown 100% sensitivity for detecting referral-worthy conditions in kids aged 2 to 8. That means it catches every true case. Its specificity is 91%-meaning it rarely flags kids who don’t need help. That’s better than most traditional methods. Studies show these devices are faster-just 1 to 2 minutes per child-and more accurate for kids under 4. The positive predictive value? 68%, compared to 52% for visual acuity tests alone. But they’re not perfect. They can overcall. A child with mild farsightedness might be flagged even if they don’t need glasses yet. That’s why follow-up with an eye doctor is still required. But catching the real problems early? That’s worth a few false alarms.

Which Method Is Better: Charts or Machines?

There’s no single winner. It depends on the child. For cooperative 5-year-olds, optotype-based screening (charts) is still the gold standard. The Sloan letters chart is preferred over Snellen because the letters are designed to be equally legible. Snellen letters vary in complexity, which can skew results. For kids aged 3 to 4, especially those who won’t cooperate, instrument-based screening outperforms charts. The Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) study found autorefractors like SureSight and Retinomax had sensitivity rates of 71% to 89%. Traditional stereoacuity tests? Only 46% to 55%. Many clinics now use a two-step approach: start with the machine. If it flags something, confirm with a chart. If the child passes the machine, they’re likely fine. This reduces false negatives and saves time. Experts like Dr. Alex R. Kemker say instrument-based screening is becoming the standard of care for kids aged 3 to 5. But Dr. Graham E. Quinn, lead researcher of the VIP study, warns: “No single test is perfect.” That’s why combining methods-especially for younger kids-is the smartest move.What Happens After a Positive Screen?

A failed screen doesn’t mean a child needs glasses or surgery. It means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. Common follow-up diagnoses:- Amblyopia: Treated with patching the stronger eye or atropine drops to blur it temporarily.

- Strabismus: May need glasses, vision therapy, or surgery to realign muscles.

- Refractive errors: Nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism corrected with glasses.

12 Comments

Look, I’ve seen too many pediatricians rush through vision screens like it’s a checkbox-dim lights, chart too close, kid crying, they just say “fine” and move on. That’s not screening, that’s negligence. The blinq™ scanner? It’s a game-changer. I work in a rural clinic-we got one last year. Kids who couldn’t even sit still? We got results in 90 seconds. No more guessing. No more “maybe next visit.” This isn’t optional-it’s medical triage. If you’re not using instrument-based tools for under-4s, you’re doing harm by omission.

My daughter was screened at age 3 and passed-but we still got referred because the machine flagged asymmetry. Turned out she had mild astigmatism. We didn’t know. She didn’t complain. She just thought everyone saw the world slightly blurry. I’m so glad we followed up. I wish every parent knew how silent these issues are. Kids don’t know what “normal” looks like. They just adapt. And that’s why screening isn’t about testing kids-it’s about protecting their future.

Okay so let me get this straight-you’re telling me we’re spending thousands on machines like blinq™ because some 3-year-old won’t point at a picture of an apple? Meanwhile, we’ve got kids in this country who can’t read because their schools don’t even have books. I mean, come on. The real crisis is systemic underfunding of education, not whether a kid sees a circle or a house. And don’t even get me started on the “AI-powered” nonsense-these devices overcall like crazy. I’ve seen 5 kids flagged for “referral-worthy” issues and only 1 needed glasses. The rest were just farsighted and growing out of it. We’re creating a medical industry around false positives. And the cost? $3,500 per scanner? That’s a luxury toy for pediatricians who don’t want to actually talk to parents.

Let’s be real-this isn’t about vision. It’s about control. Who decides what “normal” vision is? The AAP? The USPSTF? The same institutions that told us vaccines caused autism and that low-fat diets were holy scripture? Now we’re pathologizing childhood development under the guise of “early detection.” What if the brain’s ignoring one eye isn’t a defect? What if it’s an adaptation? What if the child is learning to see the world differently? We’re not saving sight-we’re enforcing conformity. And the machines? They’re just digital gatekeepers for a society terrified of neurodiversity. We’re turning kids into data points. And the worst part? We call it compassion.

Back home in Kerala, we don’t have these fancy scanners. Grandmas check kids by waving a flashlight in front of their eyes and saying, “See the red?” If one eye looks dull, they take the kid to the clinic. Simple. No charts. No AI. Just eyes and experience. And guess what? They catch the same stuff. Maybe we don’t need tech to fix what humans used to do naturally. Maybe we just need to trust caregivers again.

Screening isn’t optional. If you skip it, you’re a bad parent. Period.

I’ve worked with refugee families who’ve never heard of vision screening-language barriers, fear of doctors, no transportation. One mom cried because she thought her son was “just shy” when he wouldn’t look at the chart. We used a blinq™ scanner. He had severe amblyopia. We got him glasses in 3 weeks. He smiled for the first time. This isn’t about tech or guidelines-it’s about dignity. Every child deserves to see their mother’s face clearly. No exceptions. No excuses.

So let me get this straight-you’re advocating for mandatory screening at age 3… but we don’t mandate screening for hearing, or dental, or mental health until much later? Interesting. Why vision? Is it because it’s easy to quantify? Because you can slap a chart on a wall and call it science? Meanwhile, kids are failing in school because of untreated ADHD, anxiety, or malnutrition-and we’re throwing money at a red reflex test? I’m not against screening. I’m against the performative virtue signaling wrapped in clinical jargon. What’s next? Mandatory taste sensitivity tests before kindergarten?

Oh, darling, this is just another iteration of the neoliberal medical-industrial complex’s obsession with quantifying childhood. We’ve turned the tender, sacred act of growing up into a series of algorithmically validated benchmarks. The blinq™ scanner? A grotesque fetish object for the technocratic elite. And the parents? They’re just anxious consumers, dutifully submitting their infants to the gaze of the machine, terrified that their child’s eyes might not conform to the 20/32 ideal. We’ve forgotten that vision isn’t merely optical-it’s existential. What if the child who doesn’t see perfectly… sees more?

lol so now we’re scanning 3-year-olds with AI because parents can’t hold their kid still? My nephew passed the chart test at 4, but the machine flagged him for “asymmetry.” Turns out he was just looking at the ceiling fan. They sent us a referral letter. We ignored it. He’s 8 now, plays soccer, reads books. No glasses. The system is broken. Stop wasting money on gadgets and start teaching parents how to look at their own kids.

I lost my brother to retinoblastoma because we didn’t know. He was 4. The red reflex test? Never done. We thought his eye was just “red from crying.” Now I’m a nurse. I push screening like my life depends on it-because it does. Every kid. Every time. No excuses. Not because of guidelines. Because I’ve seen what happens when you wait.

And this is why we need training. Not just devices. Providers need to know how to use them-and how to explain the results to parents who panic. I had a mom once think “referral-worthy” meant her kid had cancer. We spent 45 minutes walking her through it. She left crying… but relieved. That’s the real work. Tech doesn’t replace empathy. It just gives us a better tool to deliver it.