Preparing a child for surgery or a medical procedure isn’t just about giving them medicine. It’s about reducing fear, preventing complications, and making sure everything goes smoothly when it matters most. Too many parents are caught off guard by what’s required-what to feed, what to stop, when to give the sedative, and why it all matters. The truth? When done right, pre-op meds can cut anxiety by more than half and reduce the chance of serious problems during anesthesia by nearly 30%. This isn’t guesswork. It’s science-backed protocol, used daily in children’s hospitals across the country.

Why Pediatric Pre-Op Prep Is Different

Kids aren’t small adults. Their bodies process medicine differently. Their brains react differently to stress. Their stomachs empty faster. Their fear responses are stronger. That’s why the same fasting rules or sedative doses used for adults can be dangerous-or useless-for children. For example, adults are told to stop clear liquids four hours before surgery. Kids? Two hours. Why? Because their digestive systems move quicker. If you follow adult rules, your child might be unnecessarily dehydrated and stressed. On the flip side, giving them juice too close to the procedure? That’s a risk for aspiration-when stomach contents get into the lungs during anesthesia. Sedatives like midazolam are dosed by weight, not age. A 10-pound infant gets a completely different amount than a 60-pound child. And here’s something many parents don’t know: some kids have paradoxical reactions. Instead of calming down, they get agitated, cry harder, or fight. That’s why the choice of medication and timing matters more than you think.The Fasting Rules: What Your Child Can and Can’t Have

Fasting isn’t just about skipping breakfast. It’s about knowing exactly what counts as a solid, a liquid, or a clear fluid. Get this wrong, and your child’s surgery could be delayed-or canceled.- No solid foods after midnight the night before for kids over 12 months. That includes milk, formula, yogurt, or even peanut butter on toast.

- Milk and formula are allowed up to 6 hours before arrival. So if your appointment is at 8 a.m., you can give formula at 2 a.m.

- Breast milk is okay until 4 hours before. So if your baby is nursing, you can feed them until 4 a.m. for an 8 a.m. procedure.

- Clear liquids-water, Pedialyte, Sprite, 7-Up, or apple juice without pulp-are allowed up to 2 hours before. Orange juice? Not clear. It has pulp. Grape juice? Too thick. Stick to what’s labeled “clear.”

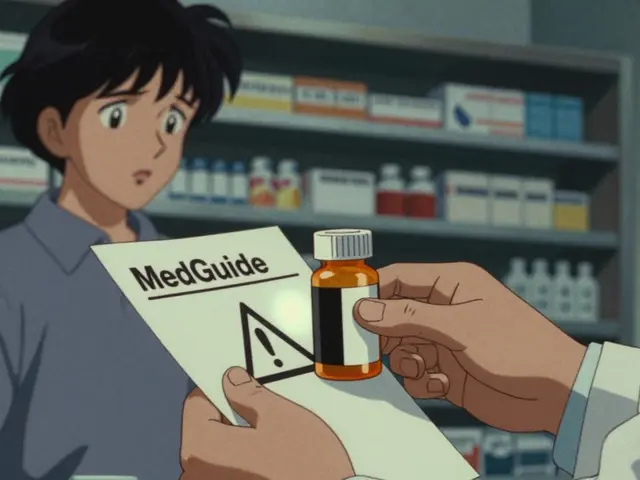

Pre-Op Medications: What’s Given, When, and Why

The most common pre-op meds for kids are oral or intranasal midazolam, and sometimes ketamine. These aren’t painkillers-they’re sedatives. Their job is to calm the child before they’re taken to the operating room.- Oral midazolam: Given as a liquid, 0.5-0.7 mg per kilogram of body weight (max 20 mg). Administered 20-30 minutes before the procedure. Works in about 15-20 minutes. Most kids get sleepy, relaxed, and forget the scary parts.

- Intranasal midazolam: Sprayed into the nose, 0.2 mg per kg (max 10 mg). Faster acting-works in 5-10 minutes. Used when a child won’t drink the liquid or is too anxious to swallow. Some kids get nasal irritation, so it’s not for everyone.

- Intramuscular ketamine: Injected into the thigh or arm, 4-6 mg per kg. Used for kids who are extremely uncooperative, have autism, or developmental delays. Takes 3-5 minutes to kick in. Kids become detached, calm, and unaware. But 8-15% experience “emergence delirium”-they wake up confused or agitated. That’s why it’s reserved for specific cases.

What Medications Should Keep Going?

This is where things get tricky. Parents often assume everything gets stopped. But some meds must continue-even on the day of surgery.- Antiepileptic drugs: If your child takes seizure meds like levetiracetam or valproic acid, give them with a sip of water on the morning of surgery. Stopping these can trigger seizures.

- Acid reducers: H2 blockers (like famotidine) or proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) help prevent aspiration. Keep giving them as usual.

- Asthma inhalers: Bronchodilators like albuterol should be given 30-60 minutes before the procedure. Kids with asthma are at higher risk for airway spasms during anesthesia. This simple step cuts complications by 40%.

- GLP-1 agonists: For older kids on medications like semaglutide (Ozempic) or exenatide (Byetta), these must be stopped 1 week and 3 days before surgery, respectively. They slow stomach emptying, which increases aspiration risk.

Special Cases: Autism, Obesity, and Other Complexities

Not all kids fit the standard profile. Some need extra planning. Children with autism spectrum disorder often react strongly to unfamiliar environments. At RCH Melbourne, 40% of autistic kids required modified protocols. One common adjustment: giving clonidine (a blood pressure medication that also calms the nervous system) 4 hours before the procedure at 4 mcg per kg. This reduces meltdowns and makes sedation smoother. Obesity changes how meds work. A 2023 multicenter trial found that standard midazolam doses were too low in 35% of obese children. The new CHOP guidelines now recommend increasing the dose by 20% for kids with BMI above the 95th percentile. This isn’t just a suggestion-it’s a safety update. Kids with pulmonary hypertension or severe asthma shouldn’t get nitrous oxide (laughing gas). It can trigger airway tightening in up to 30% of these patients. That’s why the anesthesiologist needs a full medical history before deciding on sedation type.What Happens the Night Before and Morning Of

Preparation starts long before the hospital visit.- 24 hours before: Talk to your child in simple terms. Use books, videos, or dolls to show what will happen. Avoid scary words like “cut” or “needle.” Say “medicine to help you sleep” instead.

- 12 hours before: Confirm fasting times. Write them down. Put them on the fridge.

- 6 hours before: Stop milk and formula. Keep water or Pedialyte ready.

- 2 hours before: Last sip of clear liquid. No exceptions.

- 30 minutes before: Give the pre-op medicine. Stay calm. Your anxiety is contagious.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced parents mess up. Here are the top errors-and how to dodge them:- Giving orange juice: It’s not clear. Stick to water, Pedialyte, or clear soda.

- Skipping asthma meds: One missed inhaler can mean a trip to the ICU.

- Stopping seizure meds: This is the #1 medication error in community hospitals. Always confirm with the doctor.

- Waiting too late to give sedative: If you give midazolam at 10 minutes before, it won’t work. Give it at 25 minutes.

- Not telling the team about home meds: Even supplements like melatonin or CBD can interact. Disclose everything.

What to Expect After the Medication

After the sedative, your child will likely be drowsy, maybe a little wobbly. They might not remember you leaving the room. That’s normal. The goal isn’t to knock them out-it’s to make them calm and cooperative. Some kids smile and wave goodbye. Others cry. That’s okay. The anesthesiologist will be watching their breathing, heart rate, and oxygen levels the whole time. You’ll be reunited as soon as they’re awake and stable. Post-op, up to 37% fewer children show behavioral changes like nightmares, clinginess, or fear of doctors. That’s the real win. It’s not just about the surgery-it’s about the recovery.Final Checklist: Before You Leave the House

Use this as your last-minute guide:- ✅ Fasting timeline confirmed (solid foods, milk, clear liquids)

- ✅ Pre-op medicine measured and ready

- ✅ Asthma inhaler or seizure meds packed (if needed)

- ✅ GLP-1 meds held if applicable

- ✅ Child’s favorite blanket or toy brought

- ✅ Contact info and insurance card ready

- ✅ All questions answered by the medical team

Can I give my child water before surgery?

Yes, but only clear liquids like water, Pedialyte, Sprite, 7-Up, or apple juice without pulp-and only up to 2 hours before the procedure. Avoid anything with pulp, milk, or thick consistency. Even a small amount of orange juice can delay surgery.

Is midazolam safe for toddlers?

Yes. Midazolam is one of the most studied and safest sedatives for children. Doses are carefully calculated by weight. Side effects are rare and usually mild-drowsiness, dizziness, or temporary confusion. Paradoxical reactions (acting out instead of calming) happen in 5-10% of cases, but staff are trained to handle them.

What if my child is on medication for ADHD?

Most ADHD meds like methylphenidate or amphetamines can be continued on the day of surgery. But some hospitals may ask you to skip the morning dose if it could interfere with anesthesia. Always check with your anesthesiologist-don’t assume.

Why can’t my child eat before surgery?

Food or liquid in the stomach can come up during anesthesia and enter the lungs, causing pneumonia or breathing problems. This is called aspiration. Fasting reduces that risk. Kids clear their stomachs faster than adults, so their fasting times are shorter.

What if my child is sick the day before surgery?

Call the hospital. A mild cold might not delay surgery, but a fever, wheezing, or cough could. Anesthesia is harder on a child with a respiratory infection. The team will decide if it’s safer to reschedule. Don’t wait until you get there.

9 Comments

This guide is absolutely fire. I’ve seen too many parents panic because they thought ‘clear liquid’ meant any juice that wasn’t red. Apple juice with pulp? Nope. That’s not clear, that’s a liability. One mom I know had her kid’s surgery postponed for 4 hours because she thought ‘clear’ meant ‘not murky.’ Honey, if you can see your reflection in it, you’re good. Otherwise, stick to water, Pedialyte, or Sprite. No exceptions. And for the love of all that’s holy, don’t skip the asthma inhaler. I’ve seen kids end up in PICU because someone thought ‘it’s just a little cough.’ It’s not. It’s a full-blown airway grenade waiting to go off.

Midazolam? Perfect. But dose it right. A 10-pound baby isn’t a 60-pound toddler. Weight-based dosing isn’t optional-it’s survival. And if your kid’s autistic? Clonidine at 4 mcg/kg, 4 hours out. It’s not a hack-it’s science. The hospital I work with cut meltdowns by 70% just by adding that one step. Stop guessing. Start measuring.

And yes, GLP-1 agonists? Stop them a week out. Ozempic isn’t just for weight loss-it’s a slow-mo stomach blocker. Aspiration risk spikes if you don’t. I’ve seen ERs full of parents crying because they didn’t know. Now they do. Thanks for this.

ASA guidelines updated 2023: fasting windows are now standardized across pediatric centers. Midazolam PO: 0.5–0.7 mg/kg. Intranasal: 0.2 mg/kg. Ketamine IM: 4–6 mg/kg. Any deviation = protocol violation. Obesity? BMI >95th percentile = +20% dose. Autistic kids? Clonidine protocol mandatory. No exceptions. Failure to comply = increased ASA class. Document everything. Anesthesia teams audit this monthly. You’re not helping by winging it.

Thanks for putting this together. I’m a dad of two, and honestly, I was terrified before my daughter’s tonsillectomy. I read half the stuff online and got more confused. This? This is the first thing that made sense. I wrote the fasting times on a sticky note and stuck it on the fridge. Gave her the midazolam at 25 mins before-she just smiled and cuddled me. No tears. No drama. The nurse said it was the smoothest prep they’d seen all week. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. Now I do. Really appreciate this.

Oh please. You’re treating this like some sacred ritual when it’s just pharmacology with extra steps. Parents treat pre-op like a Pinterest board instead of a clinical protocol. ‘Bring their favorite blanket’? Cute. But if you don’t know the difference between clear and non-clear liquids, your blanket won’t save them from aspiration pneumonia. And don’t get me started on the ‘emotional readiness’ nonsense. Kids don’t need therapy before surgery-they need properly dosed midazolam and a fasting window that matches their gastric emptying rate. Stop romanticizing medical care. This isn’t a Netflix special. It’s a procedure. Do the math. Follow the protocol. Stop making it about feelings.

I just want to say thank you for this. My daughter has autism, and I was so scared about the hospital. We did the clonidine thing you mentioned-and it changed everything. She didn’t scream, she didn’t hide, she just nodded and held my hand. The nurse said she was the calmest kid they’d seen all morning. I cried in the hallway afterward. This isn’t just medical advice-it’s peace of mind. If you’re reading this and your kid’s on the spectrum, please try the clonidine. It’s not magic. It’s medicine. And it works. You’ve got this.

Why are we giving kids drugs before surgery at all? This is just chemical sedation. Why not just hold them and talk to them? My cousin’s kid had surgery and they didn’t give any meds-just sang songs and held their hand. They were calm the whole time. Why do we always have to medicate? It’s wrong. Kids should be treated with love, not chemicals.

Hey Nicole-I hear you, but I’ve been in the OR when a kid’s screaming and thrashing because they’re terrified. Midazolam isn’t about ‘chemical control.’ It’s about keeping them safe. If they’re panicking, they hyperventilate, their heart races, and now you’ve got a kid with low oxygen and a full stomach. That’s not love-that’s risk. The meds let them sleep through the scary part. Then they wake up with a lollipop and a hug. It’s not magic. It’s mercy. And honestly? I’d rather my kid be calm than traumatized.

As a nurse who has worked in pediatric anesthesia for over 22 years across three continents-including the UK, Canada, and here in the States-I can say with absolute certainty that the guidelines presented here are not only accurate but are, in fact, the bare minimum of what should be expected. In India, where I trained initially, we used to rely on parental intuition-and yes, we lost children to aspiration because no one knew that milk was not a clear liquid. In Japan, we had protocols so strict we would weigh the child’s last meal to the gram. Here, we are lucky to have even this level of standardization. Please, do not underestimate the precision required. The difference between 1.9 hours and 2.1 hours of fasting can be the difference between a smooth induction and a code blue. And yes, clonidine for autistic children? Absolutely. We have data from Kyoto Children’s Hospital that shows a 68% reduction in emergent restraint events when clonidine is administered pre-op. This is not anecdotal. This is evidence-based practice. Thank you for sharing this. It is a public service.

Thank you so much for this! I’m from India and my son is having surgery next week. I was so confused about what to give him. Now I know clear juice means no pulp, and I won’t stop his seizure med. I told my wife and she cried happy tears. We’re gonna bring his toy dinosaur. He loves it. God bless you all!