Generic drugs save Americans billions every year. In 2012 alone, they cut prescription costs by $217 billion. That’s not a guess-it’s a fact from the Federal Trade Commission. But behind those savings is a quiet war: branded drug companies fighting to keep generics off the market, and regulators trying to stop them. This isn’t about innovation anymore. It’s about control. And the rules meant to protect competition are being bent, stretched, and sometimes broken.

How the System Was Supposed to Work

In 1984, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to fix a broken system. Before then, generic drugs took years to get approved. Branded companies held a monopoly long after their patents expired. The law changed that. It created a faster path for generics to enter the market through something called an Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. And to reward the first generic company that challenged a patent, it gave them 180 days of exclusive sales. That 180-day window wasn’t a gift. It was a tool. The idea was simple: let one generic company undercut prices hard, then let others follow. The result? Prices drop fast. One generic competitor can knock down prices by 20% in a year. Five? Up to 85%. By 2016, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. That’s the power of competition.The Dark Side of the Rules

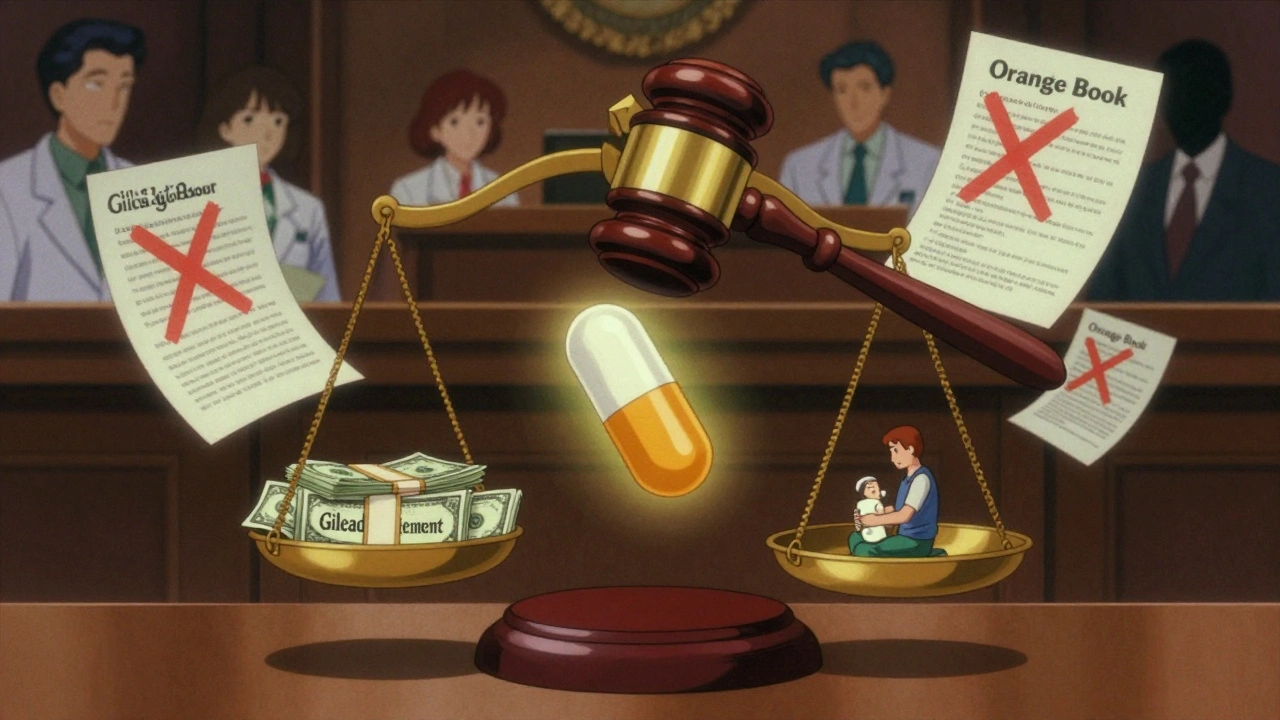

But loopholes opened up. And big pharma learned how to use them. One of the worst tricks is called “pay-for-delay.” A branded company pays a generic manufacturer to stay out of the market. Not because the generic is inferior. Not because it’s unsafe. Just because the branded company wants to keep prices high. The FTC has tracked over 18 of these deals since 2000. In 2023, Gilead Sciences paid $246.8 million to settle allegations it used pay-for-delay to block generic versions of its HIV drug Truvada. That’s not a fine. That’s a bribe. The Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that these deals could violate antitrust laws-if the payment is large and unexplained. But proving it is hard. Courts still struggle to tell the difference between a legitimate settlement and a payoff. And without clear rules, companies keep trying.Playing the Patent Game

Another tactic? Gaming the FDA’s Orange Book. The Orange Book lists every patent tied to a branded drug. Generics have to check it before filing their application. If they think a patent is invalid, they file a “Paragraph IV certification”-a legal challenge. That’s the whole point of Hatch-Waxman. But some companies abuse it. They list patents that don’t even cover the drug. Or they file patents on minor changes-like switching the pill color or shape-just to keep the list long. In 2003, the FTC took Bristol-Myers Squibb to court for listing patents that had nothing to do with the actual drug. The goal? To scare off generics. The court agreed it was anti-competitive. But it didn’t stop. Companies still do it today. Then there’s “product hopping.” A company nears patent expiration, so it launches a slightly modified version of its drug-maybe a new delivery method or a different dosage. Then it stops selling the original. Suddenly, pharmacists can’t fill prescriptions for the old version. Generics can’t step in because the original is gone. The new version? Still under patent. AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec and Nexium. Courts didn’t block it. And the tactic spread.

Sham Petitions and Disparagement

It’s not just about patents and payments. Companies also use the system to delay generics in other ways. Sham citizen petitions are one. A branded company files a complaint with the FDA, claiming a generic drug is unsafe or ineffective. Often, the claims are baseless. But the FDA has to respond. And that takes months. By the time the agency says the petition is frivolous, the generic launch is delayed. The FTC sued Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2023 for filing dozens of these petitions to block a generic version of Copaxone, a multiple sclerosis drug. The case is still open. Then there’s disparagement. Companies spread rumors. They tell doctors that generics are less effective. They whisper about side effects that don’t exist. They fund misleading studies. A 2023 report from CMS Law found this happens across Europe and the U.S. It’s not illegal-but it’s unethical. And it works. Patients don’t trust generics. Pharmacists hesitate to substitute. Prescriptions stay on the expensive brand.What’s Happening Around the World

The U.S. isn’t alone. But other countries are fighting back harder. In Europe, the European Commission has opened 27 antitrust cases between 2018 and 2022. Sixty percent were about delaying generics. They’ve gone after companies that withdraw marketing authorizations just to block generics in certain countries. Commissioner Margrethe Vestager says these delays cost Europeans €11.9 billion every year. China took a bold step in January 2025. It released new antitrust guidelines for pharmaceuticals. For the first time, they listed five “hardcore restrictions” that are automatically illegal: price fixing, market division, output limits, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. By Q1 2025, six cases had been penalized. Five were about price fixing through messaging apps and algorithms. China is even using AI to track suspicious pricing patterns in real time. The U.S. still lags. Enforcement is slow. Fines are small compared to profits. And courts are often hesitant to interfere in patent disputes.

Who Pays the Price?

These tactics aren’t just legal games. They have real human costs. In 2022, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 29% of U.S. adults didn’t take their medication as prescribed because they couldn’t afford it. Many of those drugs had generic versions waiting to launch-blocked by pay-for-delay deals or sham petitions. Prescription costs aren’t just a personal burden. They strain Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generics reduce drug prices by 30% to 90%. That’s the difference between someone taking their insulin or skipping doses. Between filling a heart medication or choosing between food and pills.What’s Next?

The FTC is pushing for change. They’ve called for reforms to the Orange Book system. They want faster review of citizen petitions. They’re pushing Congress to limit the 180-day exclusivity window so it can’t be used as a bargaining chip in pay-for-delay deals. But real change needs more than agency reports. It needs new laws. Clearer rules. And a willingness to treat these anti-competitive practices for what they are: a tax on sick people. The system was built to save lives. Now, it’s being used to protect profits. If we want generics to keep working as they should, we have to fix the rules before more people get hurt.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a faster approval process for generic drugs through Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). It also gave the first generic company to challenge a patent 180 days of market exclusivity to encourage competition. This law helped generic drugs rise from 19% of prescriptions in 1984 to 90% by 2016, saving consumers over $1.68 trillion between 2005 and 2014.

What are pay-for-delay agreements in the pharmaceutical industry?

Pay-for-delay agreements happen when a branded drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. These deals keep prices high and block competition. The FTC has pursued over 18 such cases since 2000. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these deals can violate antitrust laws if they involve large, unexplained payments-like the $246.8 million Gilead paid in 2023 to settle a similar case.

How do companies misuse the FDA’s Orange Book to block generics?

The Orange Book lists patents linked to branded drugs. Generics must review it before filing. Some companies list patents that don’t actually cover the drug’s active ingredient-like patents on packaging or manufacturing methods. This creates confusion and deters generic entry. In 2003, the FTC successfully sued Bristol-Myers Squibb for this practice, but it continues today.

What is product hopping and why is it controversial?

Product hopping is when a drug company slightly modifies its branded drug-like changing the pill form or dosage-right before its patent expires, then stops selling the original version. This makes it harder for generics to replace it, because the original is no longer available. AstraZeneca used this tactic with Prilosec and Nexium. Courts have often allowed it, even though it delays generic competition and keeps prices high.

How does China’s 2025 antitrust guidance differ from U.S. enforcement?

China’s 2025 Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector explicitly ban five practices as illegal by default: price fixing, market division, output limits, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. They’ve already penalized six cases, mostly for price fixing through apps and algorithms. Unlike the U.S., where enforcement is case-by-case and slow, China treats these as automatic violations and uses AI to detect collusion in real time.

Why do generic drugs cost so much less than branded ones?

Generic drugs don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re bioequivalent to the branded version. That cuts development costs by 80-90%. Once multiple generics enter the market, competition drives prices down-often to 80-95% below the brand name. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generics reduce drug prices by 30% to 90%.

15 Comments

This is all so exhausting. I just want my meds to be cheap and not have to read a novel to figure out why they’re not.

Why does everything have to be a corporate war zone?

yo so like the hatch-waxman act was supposed to be the hero but turns out it’s just a glorified loophole factory lmao

pay for delay? more like pay for monopoly. and orange book? more like orange lie book. they list patents on the color of the pill. i swear to god if i see one more ‘new delivery system’ i’m gonna scream. and don’t even get me started on product hopping - it’s like they’re playing monopoly with people’s insulin.

ftc? they’re out here filing reports like it’s a powerpoint presentation. we need jail time, not memos.

OK BUT LET’S TALK ABOUT THE FACT THAT ASTRASENCA DID THIS WITH PRILOSEC AND NO ONE GOT PUNISHED. NO ONE.

They took a perfectly good, $5 pill and turned it into a $300 ‘revolutionary’ pill with a different coating. A DIFFERENT COATING. And now? No generic. Just a bunch of doctors who got tricked into thinking the new version is ‘better.’

And the FDA? They just sit there like a confused librarian. This isn’t innovation. This is psychological warfare on sick people. I’m not even mad. I’m just disappointed.

And don’t even get me started on how they pay pharmacists to push brand names. It’s all rigged. Everything.

THIS IS WHY WE NEED TO FIGHT BACK 💪🔥

Generic drugs save lives. Period. 💊❤️

These big pharma giants are literally choosing profit over people. And it’s not just about money - it’s about someone skipping their heart meds because they can’t afford it. 😭

Let’s demand change. Write to your reps. Share this. Tag your doctor. We can’t stay silent. 🙌 #GenericsSaveLives #PharmaIsRigged

oh wow the ftc is ‘pushing for reform’? cute. like they’re gonna stop the same people who funded their last 3 campaigns.

and china using ai to catch price fixing? lol we’re still arguing whether ‘pay-for-delay’ counts as bribery or just ‘business strategy.’

the only thing that’s ‘hardcore’ here is how hard they’re laughing while we pay $400 for a 30-day supply of a drug that costs 8 cents to make.

congrats america, you won the race to the bottom.

and yes, i’m still mad.

The structural asymmetry in regulatory capture is profound. The Orange Book’s patent listings function as a de facto anti-competitive tool, circumventing the statutory intent of Hatch-Waxman by exploiting informational opacity.

Meanwhile, sham petitions exploit administrative burden as a weapon - a form of regulatory arbitrage that externalizes delay costs onto public health infrastructure.

And yet, courts continue to defer to patent law’s procedural formalism, ignoring the economic realities of market foreclosure.

It’s not a failure of enforcement. It’s a feature of the system.

I think a lot of people don’t realize how much this affects families. My mom’s on a generic for her blood pressure, and when it got delayed for 6 months because of some petition, she had to switch to the brand - cost tripled.

I’m not saying we should burn down the FDA, but maybe we need someone who actually talks to patients on the review board?

Just saying. We all want safe meds. But we also want them to be affordable.

Maybe we can find a middle ground?

Let’s break this down like we’re talking to a new grad in pharma policy: Hatch-Waxman = brilliant. But loopholes? They’re not bugs - they’re features designed by lobbyists.

Pay-for-delay? That’s collusion with a corporate handshake.

Product hopping? That’s a bait-and-switch with a pill.

Here’s what we can do: demand transparency in the Orange Book. Cap exclusivity windows. Penalize sham petitions with real fines - not ‘settlements’ that cost less than a CEO’s bonus.

We know the fix. We just need the will.

you know what’s really going on? it’s not just pharma. it’s the whole system. the fed, the white house, the FDA - they’re all connected to the same shadow network. these ‘patents’? they’re not even real. they’re just digital keys to lock you out of your own medicine.

and china? they’re not using ai to catch price fixing - they’re using it to track who’s talking about it online. you think that’s a coincidence? i’ve seen the documents. they’re watching us.

the real drug? it’s not in the bottle. it’s in the silence.

you’re not supposed to know any of this.

but now you do.

It is, indeed, a matter of considerable concern that the legislative architecture intended to foster competition in the pharmaceutical sphere has been systematically subverted by strategic manipulation of intellectual property frameworks.

The persistence of pay-for-delay arrangements, despite judicial recognition of their anticompetitive nature, suggests a profound institutional inertia.

One is compelled to inquire: to what extent has regulatory capture become so entrenched as to render statutory remedies impotent?

so like the whole system is just a giant scam

and everyone knows it but no one wants to say it out loud

my pharmacist just shrugs when i ask why the generic is delayed

and my doctor says ‘it’s complicated’

yeah. it’s complicated when you’re making billions off sick people

peace out

imagine if we treated this like a public health crisis instead of a legal loophole

like… if we just said ‘no more pay-for-delay’ and made it illegal tomorrow

would the world end? or would millions of people finally be able to breathe?

also… why do we let companies patent the color of a pill? 😅

someone please tell me this isn’t real life

you think this is bad? wait until you find out the FDA’s top officials all used to work for big pharma.

and the people writing the guidelines? they all got paid millions to ‘consult.’

the 180-day exclusivity? that’s not a reward - it’s a bribe waiting to be cashed in.

and china? they’re not ahead - they’re just further along in the same game.

we’re all being played.

and the worst part? you’re still taking your meds.

you’re still paying.

you’re still silent.

There is a moral economy here - one where the dignity of life is weighed against the calculus of shareholder value.

When a man chooses between insulin and rent, the system has already failed him.

Patents were meant to incentivize creation, not to erect toll booths on the road to survival.

And yet, we have allowed the law to become a language spoken only by those who profit from its distortion.

Perhaps the real question is not whether the rules are broken - but whether we still believe they should mean anything at all.

okay but like… if you’re a big pharma exec and you’ve got a drug that’s about to go generic… what’s your move?

you don’t innovate.

you don’t improve.

you just… change the color.

and then you cry when people say you’re evil.

and then you pay someone to stay quiet.

and then you get a tax break.

and then you go on vacation to the bahamas.

and then we all pay for it.

and then we wonder why healthcare is broken.

nope. we know why.

it’s not broken.

it’s designed this way.