When someone starts taking an antipsychotic medication, the goal is usually clear: reduce hallucinations, calm paranoia, or stabilize mood swings. But there’s another side to these drugs that many don’t talk about until it’s too late - metabolic risks. These aren’t just side effects. They’re life-threatening changes in how the body processes sugar, fat, and energy. And they happen faster than most people expect.

Why Antipsychotics Change Your Metabolism

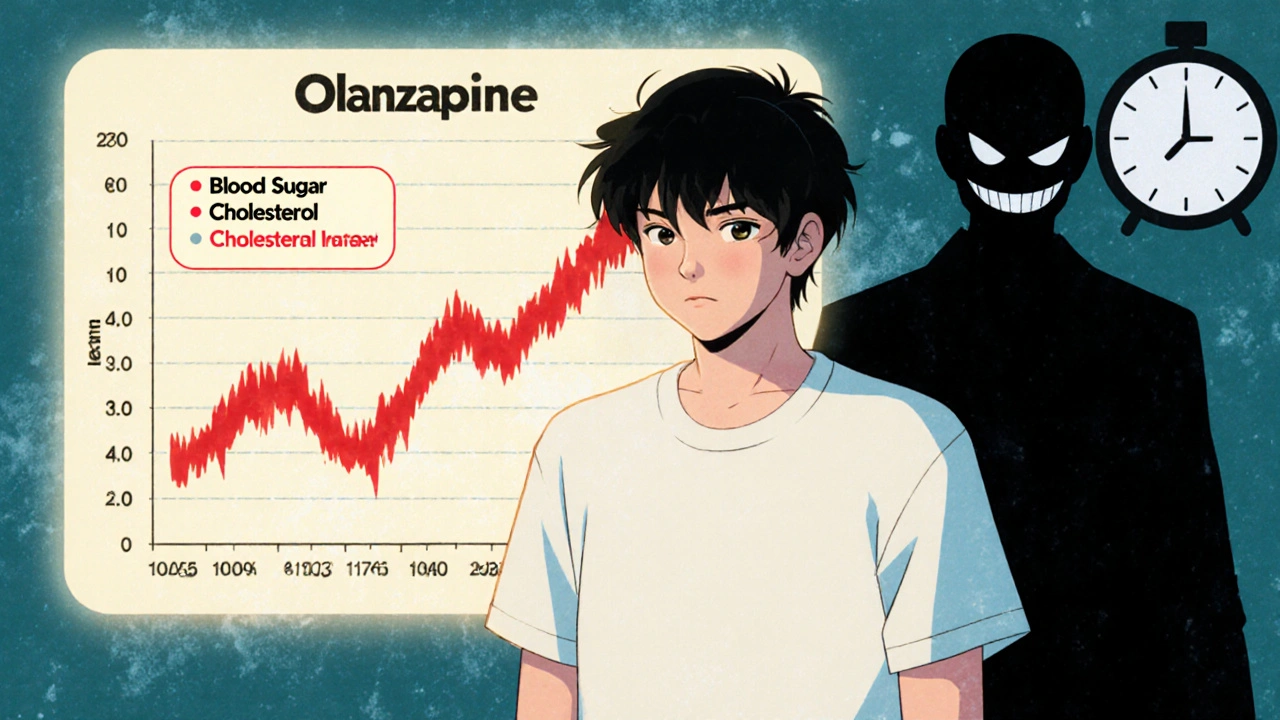

Second-generation antipsychotics - also called atypical antipsychotics - were supposed to be safer than the older ones. Less tremors, less stiffness. But they came with a hidden cost. Drugs like olanzapine, clozapine, and quetiapine don’t just affect dopamine in the brain. They mess with your liver, pancreas, fat cells, and even your appetite signals.It’s not just about eating more. These medications interfere with how your body handles glucose and fat at a cellular level. Studies show that even before you gain noticeable weight, your blood sugar and triglycerides can start climbing. That’s why someone can look fine on the scale but already be heading toward type 2 diabetes.

The risk isn’t the same for every drug. Olanzapine and clozapine carry the highest metabolic burden. In the CATIE study, patients on olanzapine gained an average of 2 pounds per month. By the 18-month mark, 30% had gained so much weight that it became a reason to stop taking the medication. That’s not rare. That’s the norm for these drugs.

What Metabolic Problems Are We Talking About?

Metabolic syndrome isn’t one thing. It’s a cluster of five warning signs:- Extra fat around your waist (more than 40 inches for men, 35 for women)

- Triglycerides above 150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol below 40 mg/dL (men) or 50 mg/dL (women)

- Blood pressure at or above 130/85 mmHg

- Fasting blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or higher

If you have three or more of these, you have metabolic syndrome. And if you’re on an antipsychotic like olanzapine or clozapine, your chance of having this condition jumps to between 32% and 68%. Compare that to the general population, where it’s around 3.3% to 26%. That’s a threefold increase.

And it’s not just about feeling sluggish. People with metabolic syndrome are three times more likely to have a heart attack or stroke. Their risk of dying from cardiovascular disease rises sharply - even within just seven years of diagnosis.

Which Antipsychotics Are Safer?

Not all antipsychotics are created equal when it comes to metabolism. Some are much gentler on your body.High-risk drugs:

- Olanzapine - biggest weight gain, highest blood sugar spikes

- Clozapine - very effective for treatment-resistant psychosis, but metabolic damage is common

Moderate-risk drugs:

- Quetiapine

- Risperidone

- Asenapine

- Amisulpride

Lower-risk options:

- Aripiprazole

- Lurasidone

- Ziprasidone

Ziprasidone and lurasidone, for example, are often chosen for patients who already have prediabetes or high cholesterol. They don’t cause much weight gain - sometimes none at all. But they’re not always the best choice for severe psychosis. That’s the trade-off.

Monitoring Isn’t Optional - It’s Life-Saving

Guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association and the American Diabetes Association are clear: every person starting an antipsychotic needs a baseline metabolic check - and then regular follow-ups.Here’s what should happen:

- Before starting: Measure weight, BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, and lipid panel (cholesterol and triglycerides).

- At 4 weeks: Check weight and blood pressure. Look for early signs of glucose changes.

- At 12 weeks: Repeat fasting glucose and lipid panel. Compare to baseline.

- At 24 weeks: Full metabolic panel again.

- Every 3-12 months after that: Ongoing monitoring based on risk level.

It’s shocking how often this doesn’t happen. Many patients get their first antipsychotic prescription and never have their blood sugar checked again for years. That’s dangerous. Metabolic damage can start within weeks - long before you notice you’ve gained weight.

What Happens If You Don’t Monitor?

The consequences aren’t theoretical. People on long-term antipsychotics die 15-20 years earlier than the general population. The leading cause? Heart disease and diabetes - both preventable with proper monitoring.And it’s not just physical health. Weight gain is one of the top reasons people stop taking their meds. Studies show 20% to 50% of patients with schizophrenia quit their medication because of weight gain. That leads to relapse, hospitalization, and lost jobs or relationships.

Imagine being told your medication is working - but your body is falling apart. You feel guilty for gaining weight, even though it’s the drug, not your willpower. Then you stop taking it, and your psychosis comes back. It’s a cycle that traps too many people.

What Can You Do About It?

The good news? You’re not powerless.1. Lifestyle changes help - but they’re not enough alone. Diet and exercise are critical. A structured program with a dietitian and a personal trainer can cut weight gain by half in some cases. But if you’re on olanzapine, even perfect habits might not stop the metabolic shift.

2. Medication switches are possible. If you’re gaining weight fast and your psychosis is stable, talk to your psychiatrist about switching to a lower-risk drug like aripiprazole or lurasidone. It’s not giving up - it’s protecting your long-term health.

3. Use long-acting injectables wisely. Some think shots are safer. They’re not. LAIs don’t reduce metabolic risk. You still need the same monitoring.

4. Get support. Many clinics now offer integrated care - where a psychiatrist, a diabetes educator, and a nutritionist work together. That’s the gold standard. If your provider doesn’t offer this, ask for a referral.

The Bottom Line

Antipsychotics save lives. But they can also shorten them - if you don’t pay attention to the body’s warning signs. The key isn’t avoiding these medications. It’s using them with eyes wide open.If you or someone you care about is on an antipsychotic, ask these three questions:

- What’s my baseline metabolic number? (Weight, blood sugar, cholesterol)

- When’s my next check-up? (Not in six months - in four weeks.)

- Is there a lower-risk alternative if things start going wrong?

There’s no shame in wanting to live longer. And there’s no excuse for not monitoring.

Do all antipsychotics cause weight gain?

No. While many second-generation antipsychotics like olanzapine and clozapine cause significant weight gain, others like aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone have much lower metabolic risks. Weight gain varies widely by drug, and some patients gain little to no weight even on higher-risk medications.

How soon do metabolic changes start after starting an antipsychotic?

Metabolic changes can begin within the first few weeks - sometimes before any noticeable weight gain. Blood sugar and triglyceride levels often rise before the scale moves. That’s why early monitoring at 4 weeks is critical.

Can I switch to a different antipsychotic if I’m gaining weight?

Yes, if your symptoms are stable. Switching to a lower-risk medication like aripiprazole or lurasidone is a common and safe strategy. This should be done under the supervision of a psychiatrist to avoid relapse. The goal is to balance mental health stability with long-term physical health.

Are long-acting injectables safer for metabolism?

No. Long-acting injectables (LAIs) deliver the same active drug as oral versions, so their metabolic risks are identical. The route of administration doesn’t change how the drug affects your liver, pancreas, or fat cells. Monitoring is just as important with shots as it is with pills.

What if my doctor doesn’t monitor my blood sugar or cholesterol?

Don’t wait. Ask for a baseline metabolic panel before starting the medication, and request follow-ups at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. If your doctor doesn’t offer this, ask for a referral to a primary care provider or a clinic that specializes in psychiatric metabolic care. Your physical health matters just as much as your mental health.

11 Comments

Bro this hit different 😔 I started on olanzapine last year and my doc never checked my sugars till I passed out at work. 4 months in. My HbA1c was 7.2. They just said 'maybe eat less pizza'... like I didn't already know that. Now I'm on aripiprazole and my energy's back. Still tired but at least I'm not diabetic.

Monitoring isn't optional. It's non-negotiable. If your provider isn't doing baseline labs and follow-ups at 4, 12, and 24 weeks, find a new one. This isn't opinion-it's ADA/APA protocol. Your life isn't a gamble.

It’s fascinating, really-the existential weight of pharmaceutical intervention. We are told to surrender our biology to molecules designed to quiet the mind, yet the very act of silencing psychosis awakens a slow, cellular rebellion. The body, that ancient temple, begins to metabolize its own salvation into a slow-motion collapse. Olanzapine doesn’t just alter dopamine-it rewrites the covenant between self and flesh. And we call it treatment? Or is it quiet surrender dressed in white coats and insurance codes?

Where is the ethics in prescribing a drug that trades sanity for a future of statins, insulin pens, and silent heart attacks? We’ve turned psychiatry into a metabolic gamble, and the house always wins.

And yet-we still need them. The paradox is beautiful. And tragic. And utterly human.

Metabolic syndrome incidence on SGAs is well-documented in RCTs and real-world cohorts. The mechanism involves H1 receptor antagonism, 5-HT2C inhibition, and peripheral insulin resistance. Early detection via fasting glucose and HOMA-IR is critical. LAIs offer no metabolic advantage-same pharmacokinetics. Switching to aripiprazole or lurasidone reduces weight gain by 40-60% in longitudinal studies. Protocol adherence is the gap.

this is so important thanks for sharing. i wish more docs knew this. my cousin was on clozapine for 3 years and no one checked her lipids till she had a stroke at 31. its insane.

Bro in India we don't even get basic labs! My friend’s sister on risperidone gained 40kg in 8 months. Doctor said 'take more walk'. Walk? She can't even climb stairs. No sugar test. No cholesterol. No waist measurement. Just 'you are lazy'. How many die like this? We need awareness. Not just meds.

Why are people still on olanzapine? It’s 2025. We have better options. If you’re gaining weight and your psychosis is stable, you’re not ‘doing your best’-you’re being neglected. Stop accepting mediocrity. Demand a switch. Your heart isn’t expendable.

Look. I get it. You want to live. But let’s be real-most people on these meds are already broken. They don’t care about cholesterol. They care about not hearing voices. So yeah, maybe they die at 50. At least they died sane. That’s the trade. Don’t moralize their suffering.

Been on ziprasidone for 5 years. Zero weight gain. Sugar’s normal. My doc checks me every 6 months. Easy. If your doc isn’t doing this, they’re not doing their job. Simple as that.

Thanks for this. I’ve been telling my sister to ask for labs but she’s scared to push back. I’m gonna print this out and hand it to her. She’s on quetiapine and just started gaining weight. She thinks it’s her fault. It’s not.

Man i read this whole thing and i just wanna hug everyone who’s been through this. i’m on aripiprazole now and i still get weird guilt about my weight even though i know it’s the meds. my mom says ‘just eat less’ like its that simple. but the cravings? the fatigue? the brain fog? no one talks about that. i started walking 20 mins a day and it helped a lil. but i still wish someone had told me earlier to ask for a switch. i’m 28 and already feel like my body’s betraying me. you’re not alone. and you’re not lazy.